Lou Stoppard developed a research project on the link between Annie Ernaux’s writing and photography. As a starting point, she studied Journal du Dehors and examined the author’s writing through the prism of the history of street photography in France, drawing on the extensive collections of the MEP.

Part chronicle, part diary, Journal du Dehors is a seven-year chronicle of a life in the Paris suburbs as experienced by the author.

Lou Stoppard at the MEP : Annie Ernaux and photography

From the 4th to the 30th of April 2022, the MEP welcomed the British curator Lou Stoppard for a curatorial research residency about the MEP’s collections. Here are the results of her research.

Chronicle — Lou Stoppard

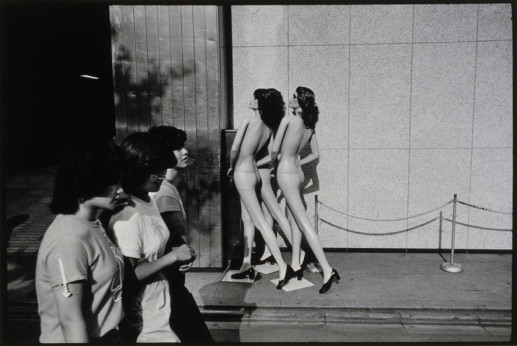

Collection MEP, Paris. Acquis en 1985 © Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris

“I believe that desire, frustration and social and cultural inequality are reflected in the way we examine the contents of our shopping trolley or in the words we use to order a cut of beef or to pay tribute to a painting; that the violence and shame inherent in society can be found in the contempt a customer shows for a cashier or in the vagrant begging for money who is shunned by his peers – in anything that appears to be unimportant and meaningless simply because it is familiar or ordinary. Our experience of the world cannot be subject to classification. In other words, the feelings and thoughts inspired by places and objects are distinct from their cultural content; thus a supermarket can provide just as much meaning and human truth as a concert hall.” – Annie Ernaux, Exteriors (Journal du Dehors).

In March, I undertook a month-long residency at the MEP, exploring the links between the writings of Annie Ernaux and photography. I focused, specifically, on Ernaux’s book Exteriors (Journal du Dehors, in French). It is a little book, of less than 100 pages, that is comprised of seemingly random journal entries – Ernaux’s observations on contemporary living on the outskirts of Paris, in Cergy-Pontoise – made over seven years, between 1985 and 1992. Youngsters dawdle. Shopkeepers go through the familiar tussle of serving their customers; joking, performing, flattering. Men salivate over young women. Women judge others on the metro.

Photography has always been a presence in Ernaux’s work; a subject matter, a prompt, a point of intrigue. References to her own family portraits – including images of herself as a child and young woman – appear in many of her books; they are like sources or markers, evidence of past selves, a tool to reinforce her sense of reality, and, in turn, the relentless slipperiness of memories. In 2005, Ernaux even authored, in collaboration with Marc Marie, a book, L’Usage de la Photo, which deals more explicitly with photography (and related themes of memory, survival, identity, perhaps even legacy). In L’Usage de la Photo (not yet translated into English), Ernaux’s text is organized around fourteen different photographs of rooms, each taken after a night of love-making.

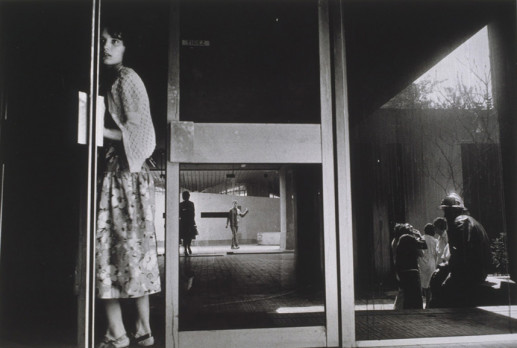

Collection MEP, Paris. Don de l’auteur en 2014 © Marie-Paule Nègre

Ernaux’s celebrated book The Years (Les Années), which sits somewhere between a memoir and a history of the years between 1941 to 2006 – a collage of forgotten customs, once-trendy objects, brands, songs and adverts, past sayings and ways of speaking – contains numerous descriptions of photographs. The book begins with the sentence: “All the images will disappear.” Ernaux then includes short fragments of personal recollections (‘a man passed on the pavement in Padua in the summer of 1990’, ‘the majesty of the elderly woman with Alzheimer’s’), alongside scenes from television and popular culture (‘the tearful face of Alida Valli as she danced with Georges Wilson in the film The Long Absence) and customs (‘turns of phrase that others used without a thought’). And yet she summarizes these diverse things with the word ‘images’, rather than ‘memories’, or, say, ‘traditions’ or ‘moments’. Images – the connotation not just of an event, but a resultant object, or artefact. Something readable, something that could be held or handled, something that could be – if the inclination was there – saved.

And yet Exteriors is different. It seems to me that within this work photographs are not treated as a subject matter or prompt; instead the texts seem to actually become photographs; objects, within a frame, which the reader – or ‘viewer’ – can both observe and step into. One is both distant and involved, seeing and imagining, present and recalling. And yet, one is simply encountering a scene, an image. In the opening pages of the book, Ernaux explains directly how she was trying to capture the abilities and properties of photography in her writing.

“I have sought to describe reality as through the eyes of a photographer and to preserve the mystery and opacity of the lives I encountered. (Later on, in New York, when I came across Paul Strand’s photographs of the inhabitants of the Italian village of Luzzara, powerful, almost painfully intense pictures – the stark characters are there, simply there – I believed this was the ideal vision of writing: inaccessible.)”

Collection MEP, Paris. Acquis en 1999 © Noshka van der Lely

Her texts are short, descriptive, evocative but never poetic or eager to seem emotive:

“The lights and clammy atmosphere of the Charles-de-Gaulle-Étoile station. Women were buying jewellery at the foot of the twin escalators. In one corridor, on the ground, in an area marked out by chalk, someone had scribbled: “To buy food. I have no family.’ But the man or woman who had written that had gone, the chalk circle was empty. People avoided walking across it.’

From an essay a student was reading on the RER, between Châtelet-les-Halles and Luxembourg, one sentence stood out: “Truth is related to reality.”“

I became intrigued by the idea of comparing the texts with photographs, of placing them next to images; what would this process reveal about how we treat literature, as opposed to photography? What would it expose about the expectations and ideals we project onto each media? This was the starting point for my residency at MEP.

I was honoured to have the chance to discuss the project with Ernaux herself and was struck by the way she described the synergy between photography and writing. She said (translated from French): “When I write, I try to give the weight of reality. Reality grips you. You are, somewhere, almost prisoner to it. And so writing, the point is to render what it holds, what monopolizes you, what grips you. That the words be like photos in which we are literally monopolized, fascinated. It’s the fascination with the real. Fascination.” She talked of the idea of writing as a way of creating markings; “To set stones down”, and noted that you can also find this in photography; the sense of evidence, recordings, remembrance – a process of giving dignity and a certain immortality to subjects.

Ernaux and I discussed the difference between seeing and reading, and seeing and writing. Can you see a text? Can you read a photograph? How do we treat photographs and texts differently? Do we presume a text has more narrative, or more bias, than a photograph? Do we presume that texts can never have the same objectivity of photographs? And, could you say that, with Exteriors, rather than writing texts, Ernaux was actually making images?

Collection MEP, Paris. Don de l’auteur en 1990

©︎ Issei Suda courtesy of Akio Nagasawa Gallery

This became the crux of my project; to treat Ernaux’s passages in Exteriors as photographs.

I began my research in the MEP Library, looking at the extensive collection of photobooks contained within it. I focused, at first, on the French history of street photography – browsing the work of known greats such as Sabine Weiss and Eugène Atget. Obviously, there is a rich history of flaneur-ism within France, so it seemed, to me, an ideal starting point. But after meeting Ernaux in Cergy, a week or so into my residency, and discussing with her the limitations of the “picturesque”, I decided that this was too narrow of a starting point, and that what I should be searching for was an ethos – a way of looking, and seeing – within certain photographers’ work, rather than a specific time period or nationality or location (after all, the Strand images Ernaux mentions are shot in Italy, in the 1950s). So, whilst I was happy to consider projects about France and Paris, I didn’t want my focus to be too geographically specific, as Exteriors is informed greatly by the sense of distance, strangeness, separation; Cergy is, Ernaux writes:

“A place suddenly sprung up from nowhere, a place bereft of memories….a place with undefined boundaries.”

It was in opening up my search that I found projects that really seemed to illuminate Ernaux’s text, and, in turn, be illuminated by it; Daido Moriyama’s images of Hawaii, and, of course, his native Japan. Mohamed Bourouissa’s astounding book, Périphérique, in which the recognizable codes of historical paintings are repurposed in photographs depicting contemporary life in the banlieus. Some of Lou Stoumen’s images of Time Square. Harvey Benge’s poignant attentiveness to day-to-day beauty, the tenderness of home and routine, and the visual language of streets, shops and public spaces, shown in books such as Truth and Various Deceptions, Small Anarchies from Home and Text Book. Yosuke Yajima’s elegant, yet quietly unsettling, exploration of Toyko suburbia in Ourselves/1981. Derk Zijlker’s optimistic photo study of Charleroi, Belgium, voted the ‘ugliest city in the world’ by a Dutch newspaper in 2008. And Felipe Abreu’s São; an exploration of growth, displacement and modernity in São Paulo, Brazil (the latter four photographers are all represented in the Self Publish be Happy photobook collection, which was recently acquired by the MEP Library).

Collection MEP, Paris. Acquis en 2019

© The Estate of Henry Wessel, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Köln

I never looked for images that illustrated Ernaux’s texts – though of course there were moments of visual coincidence (train stations, supermarkets, shoppers). Instead, my focus was on searching for a shared intention, a similar spirit, or drive. I looked for synergy, not just in terms of theme and subject matter – though of course, I was intrigued by projects that looked at place, home, commerce, the language of advertising, the rituals of day-to-day-life – but also in terms of ethos; “the inaccessibility” Ernaux describes. The sense of a suspension of moral judgement, a simultaneous acceptance of, and intrigue in, how things are. A focus on reality. A desire to say; this is what it was. This is it.

Increasingly, I found that many of the works I was attracted to in the library were represented in the MEP Collection, and decided to refocus my attention there. I felt that I needed a framework for the research – a set of boundaries that could move the project forward. I liked the idea of using a collection as the basis for this project – given that the past, the weight of history, the significance of ‘evidence’ (a word Ernaux often uses) – is such a feature within Ernaux’s writing. And so, I spent my last weeks browsing the MEP collection (which contains some 20,000 prints) and, eventually, selected around 200 photographs, from 26 different photographers, that, in my mind, relate in an interesting manner to Exteriors. The selected images date from the 1940s through to the early 2000s, and include work made in France, England, Japan and America, amongst other locations. A small selection is shown here.

Collection MEP, Paris. Acquis en 1979 © Chris Dityvon

Certain key projects or image-makers from the Collection were pivotal to my research. I interpreted a synergy between Ernaux and Henry Wessel, and his Incidents series (featuring California): the questioning of the boundaries and requirements of narrative, and the interest in seemingly random fragments of equally random lives. I was also particularly struck by the work of Bernard Pierre Wolff – whose work is sadly underappreciated (Wolff died of AIDS in 1985, leaving his archive to the MEP) – especially his desire to capture those moments or figures who are often overlooked or ignored (something Ernaux discussed, in our interview, as also being central to her work). I admired Wolff’s keen eye for the performance of status, of gender, of power and position. I was also very taken with the MEP’s collection of works by Dolores Marat and Issei Suda. I enjoyed the experience of viewing prints of famous photographs I have long loved – by the likes of William Klein and Garry Winogrand – and also discovering gems I had not seem before, great depictions of the violence and beauty of day-to-day life, captured by talents such as Kheng-Li Wee and Claude Dityvon.

I began to see my research as a threefold experiment: A project about the links between literature and photography. A project about the rich history of street/observational photography – and the myriad ways photographers have approached subjects and spaces (and thus, a celebration of the MEP Collection). And a project about Annie Ernaux and about the quest to write as if one is making photographs.

Now my month at MEP is complete, my intention is to continue my research. I plan to send my image selection to Ernaux, who has kindly offered to share with me her reactions. I would also like, in the future, to develop an exhibition; I believe that by displaying the texts, as photographs, within a gallery space, alongside photography, one could continue this examination of the relationship between literature and photography, proposing importance questions about the way writers and photographers have made work, and the way we, readers and viewers, treat and encounter words and images. I believe the exhibition would allow me to invite others to ask their own questions about the habits of thinking that shape how we view, how we see, what we believe, what moves us. What are we searching for, when looking at evidence of the lives of others? As Ernaux writes, in Exteriors:

“It is other people – anonymous figures, glimpsed in the Metro or in waiting rooms – who revive our memory and reveal our true selves through the interest, the anger or the shame that they send rippling through us.”

Biographie

© Nik Hartley

Lou Stoppard is a London-based writer and curator. She has written for The Financial Times, Aperture, The New York Times and The New Yorker. Between 2011 and 2017, Stoppard worked at the fashion and moving image website SHOWstudio, serving as the platform’s editor for a number of years. She has curated a variety of exhibitions including North: Fashioning Identity, an exploration of visual representations of the North of England, at Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool and Somerset House, London, and The Hoodie, at Het Nieuwe Institute, Rotterdam. Her recent books include a survey of the work of the British female street photographer Shirley Baker (Mack, 2019), and Pools, an exploration of swimming in photography, (Rizzoli, 2020).

© Nik Hartley